Emily Wegrzynowicz

Assistant Production Dramaturg

Aimee Jaske

Production Dramaturg

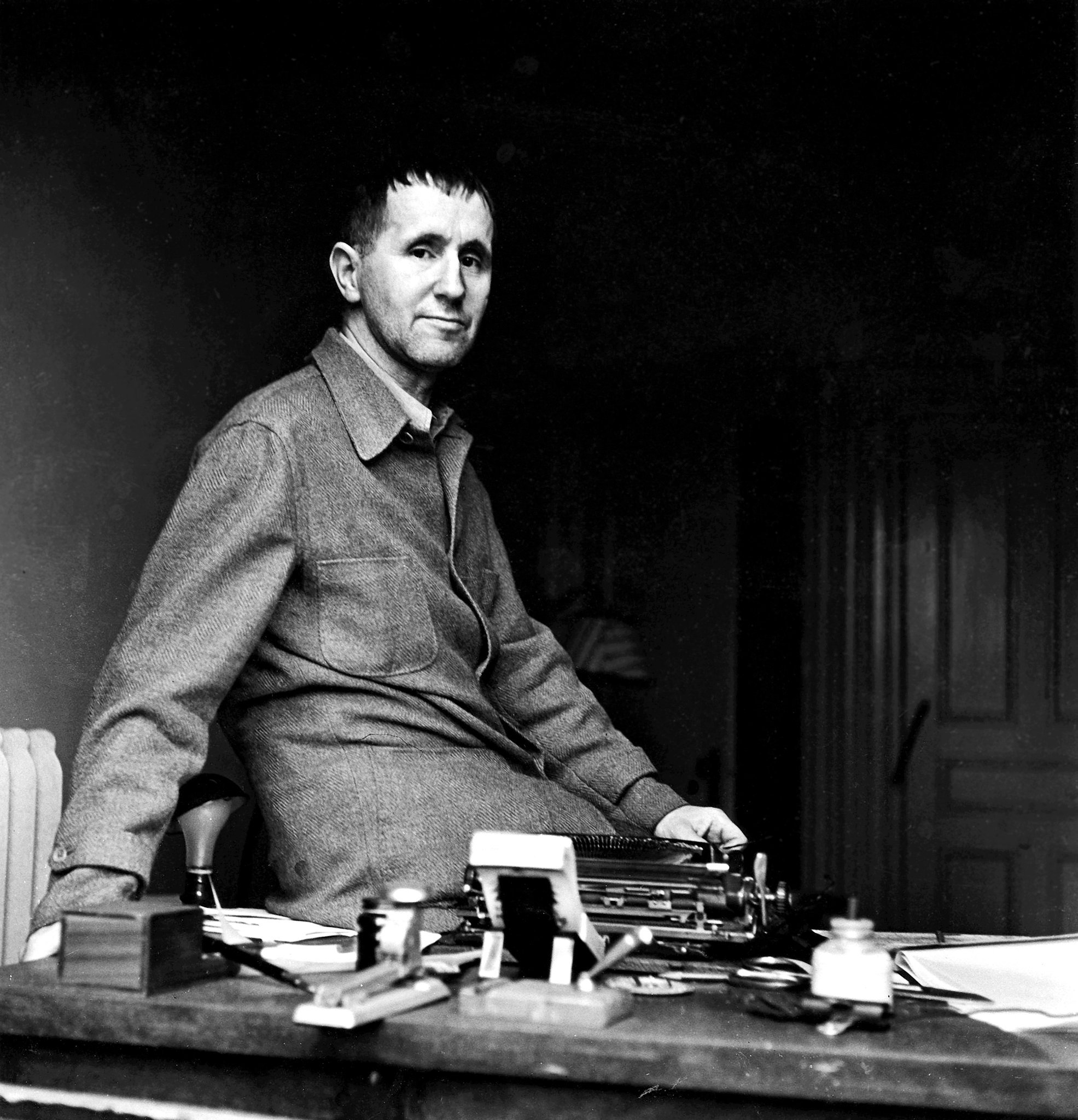

Brecht

Biography

Brecht was born in Germany in 1898. He initially studied medicine, becoming involved in an army hospital in 1918—it was during this period that he published his first work, Baal. Along with multiple plays, Brecht also released collections of poems and songs.

In the 1920s, Brecht became politically active. Learning about Marxism from important Marxist figures, such as Karl Korsch, Brecht injected his personal beliefs on the state of the government into his works moving forward.

In 1933, Brecht escaped Germany and went into exile in Scandinavia and then the US—in Germany, his books were burned, his theatre was banned, and his citizenship was withdrawn. The plays he produced in his exile would become his most popular—Mother Courage and Her Children, The Good Woman of Setzuan, and The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui, for example.

However, he was pressured to move from the US as well—he was labeled as a communist threat during the Red Scare following World War II. He even had to give evidence of his activities to the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1947 to prove he was not a danger.

In 1949, Brecht returned to Germany to start his own theater company in Berlin (the Berliner Ensemble). He died of a heart attack in 1956 (Britannica).

Epic Theatre

Brecht wrote The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui in 1941 while exiled in Finland. With an American audience in mind, the play was never actually produced in his lifetime, despite his attempts for it to be showcased on an American stage. Brecht felt like he could not produce it in his home country of Germany, where he stayed for the rest of his life following the defeat of Hitler, as he believed the Germans could not stomach seeing Hitler be mocked. However, the first performance was in Germany, as after his death, Brecht’s theater company performed the play in 1958.

In the 1960s, the play left Berlin, with his theater company touring to London. Several notable productions occurred in England—1969 with Leonard Rossiter, 1978 with Simon Callow, 1987 with Griff Rhys, and 1991 with Anthony Sher.

The play went on to be performed with newer politics in mind. Brecht’s ability to satirize a dark time in history was both praised and criticized, but his work survived all opposition. Brecht’s plays, as well as his invention of Epic Theatre, are some of the most influential to this day.

Brecht was a large influence in “Epice Theatre”, a form of theater that rivaled the naturalistic realism popular at the time. In this realistic, “dramatic” theater, the main job of the audience is to feel for the characters and empathize with their story. Brecht, however, focused on thinking about the play—he wanted the audience not to empathize but rather rationalize what they were seeing in order to make solid conclusions. To do this, he used theatrical elements to remind the audience that they were not watching real life but were watching a play. Actors giving lectures, songs, exposing of stage lighting and sound, and captions or projections, all took the audience out of the “immersion” of dramatic theater. This alienation of the audience from the play, also called verfremdungseffekt,, is what Brecht became known for (BBC).

Production History

Trap Door Theatre

Jobsite Theatre

Sydney Theatre Company

Radio Shows

Following government-sanctioned restrictions on broadcasting during World War 1, radio stations began experimenting with their programs in the early 20th Century. 1920 saw the first commercial radio station with Pittsburgh’s KDKA, and by 1939, 80% of households owned a radio—that’s 28 million (PBS)! Some of these stations broadcasted “radio dramas”, or the use of voice actors and Foley effects to tell a story. Popular dramas such as “Our Gal Sunday”, “One Man’s Family”, and “The Lone Ranger” drew families in for a night of entertainment. With time, the productions became more theatrical. One could be in a studio audience and watch a Shakespeare adaptation, a mystery, or a sketch comedy (among other genres) be recorded live (Bush).

With the introduction of visual entertainment, like television and movies, radio shows declined in the mid-20th Century. And, currently, younger generations mostly listen to podcasts, audiobooks, and music streaming apps, skipping the radio altogether.

History

Examples

Organized Crime

History

Organized crime in the 1920s-1930s included smuggling, blackmail, government corruption, theft, prostitution, kidnapping, and murder.

While gangs and mobsters existed before the 1920s, the Prohibition era—the period in America (1920-1933) that saw the banning of all alcohol—saw an exponential rise in gangster activity. Even the smallest of gangs saw an opportunity to gain money and power by illegally distributing beer, wine, and hard liquor (also known as “bootlegging”).

However, they couldn’t do it alone. Lawyers to defend arrested gangsters, police to look the other way, boat captains to smuggle alcohol from other countries, bar owners to run “speakeasies” (bars or clubs that secretly sold alcohol), and citizens willing to break the law were all necessary to the cause (The Mob Museum).

There was also an ethnic factor to gangs. Being mainly children of immigrants, gangs generally consisted of the same identities—Italian, Jewish, Polish, and Irish mobs were the most common. While some groups were rivals, some actually worked together—providing protecting meant having protection (PBS).

Chicago and Al Capone

It’s impossible to talk about 1920s mobs without talking about Chicago. With an estimated 1,300 gangs active in the mid-1920s, Chicago was alongside New York as a hub for illegal activity (FBI). Additionally, Chicago was home to the most notorious gangster of all—Al Capone.

Capone was born in 1899 in Brooklyn, New York. His life of crime began when he joined a gang in sixth grade and climbed the ladder of power and notoriety. In 1920, Lucky Torrio—another infamous mobster—invited Capone to join him in Chicago. After Torrio was wounded in 1925, Capone took over his place as boss, spreading into the suburb of Cicero (FBI).

Capone was notoriously ruthless, with estimates of 200 murders being attributed to him (either directly or at his command) (Nicholas and Chen). Most famously, Capone was widely credited for arranging the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre, a shooting that killed 7 members of a rival gang—though it was never proved. In a garage in the North side of Chicago on Valentine’s Day of 1929, 7 men of Bugs Moran’s gang were lined up against a wall and shot with Tommy guns (a submachine gun popular with gangs). Because the assailants were dressed as police officers, the 7 men put up no fight, presumably thinking they were being raided. Capone, though suspected of orchestrating the massacre, was in Florida at the time of the killing. Federal agents, knowing they had no evidence for this incident, built a case for tax evasion instead. Capone was convicted in 1931 to 11 years in prison, much of which he spent in Alcatraz (St. Valentine’s Day Massacre). However, in 1939, Capone’s health was so dismal—he suffered a late stage case of Syphillis—that he was allowed to retire to his Florida estate to live out the last 8 years of his life. He died in 1947 of cardiac arrest attributed to his disease (Britannica).

Chicago in 1920s

Al Capone

Chicago in 1920s

Police Reenactment of the Massacre

Characters | Figures

Characters

-

Early Life: Born in 1889 in Austria, Hitler feared his father (who died when he was 14) and loved his mother (who died when he was 18). He never progressed passed secondary school, as he was rejected from his dream plan of joining art school.

Military Service: Originally denied due to "unfit" health, Hitler petitioned and successfully joined the Bavarian Reserve Infantry Army in 1914. He was awarded an Iron Class award for his "bravery".

Rise to Power: After the war, Hitler joined the Munich branch German Workers' Party--later changed to "National-sozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei", or, the National Socialist German Workers’ (Nazi) Party. Initially in charge of the propaganda, Hitler began to rise in power in the Party, using "strong arm" squads to protect himself and attack his enemies. In 1921, he became leader of the Party after threatening that he would leave, as he convinced the Party that they would fail without him.

Mein Kampf: Hitler was imprisoned for treason in 1923 after he attempted to started a national revolution using his influence. While in his 9 month sentence, Hitler wrote part of his manifesto, Mein Kampf ("My Suffering"). Mein Kampf detailed his extremist ideas of race/ethnicity--he believed that the "Aryan race" (actually taken from the hypothesis that a light-skinned people moved into Ancient India), or, white people, were racially superior. He also detailed his hatred of Jewish people, often calling them "parasites".

Propaganda: Using fear tactics, Hitler convinced both the citizens and the leaders of the country that he would save them from the threat communism. And, in 1933, Hitler was appointed Chancellor of Germany.

Dictatorship: The Reichstag Fire--the burning down of the German parliament building by a "supposed" communist--convinced the government that Hitler would eradicate communism if he had more power. The "Enabling Bill" was soon passed, giving Hitler full control of Germany alongside president Hindenburg, though, at 85, Hindenburg did little to oppose Hitler. 3 months later, all non-Nazi segments of the government ceased to exist. Hitler took credit for a rise in the economy and a decrease in unemployment, resulting in a 90% voter support rate.

Conquests: In 1938, Hitler set out to first take over Austria. After the chancellor refused to sign a treaty allying with the Nazi Party, Hitler sent troops to invade Austria. He eventually annexed the country. In 1939, Hitler invaded Czechoslovakia, Lithuania, and finally, Poland. His march into Poland officially set Britain and France against him--World War II began.

World War II: Hitler planned to invade the Soviet Union with Japan and Italy as his allies. And, when Japan bombed Pear Harbor in 1941, he declared war against the United States.

The Holocaust: Following through on his plans to solidify the "Aryan" race, Hitler began to expel Jews or force them into "ghettos"--districts that isolated Jews and forced them to live in horrible conditions--in the early years of the war. Concentration camps, some previously imprisoning Socialists or political opponents, transitioned to imprisoning mainly Jews, though other minority groups--Roma, Slavic, disabled, homosexual, and Catholic individuals, among others--were also held. Concentration camps, while resulting in death through starvation, over exhaustion due to forced labor, or illness, were not created with the sole purpose of killing. The first death camp was created in 1941 in Chelmno, Poland. These death camps were influenced by earlier Nazi eugenic practices--"euthanasia" projects, as they called it, involving gassing disabled individuals with Zyklon B (a pesticide) to murder them. In death camps, upon stepping off the train used to transport them, individuals immediately had their possessions taken and were crowded into gas chambers where they were gassed with Zyklon B. Their bodies were then taken to on-site crematoriums (Holocaust Museum). Outside of these camps, Hitler organized shooting squads dedicated to killing villages full of people and burying them in mass graves--an estimated 2 million Jewish people were killed this way. In total, 6 million Jews were systematically killed in what is now known as the Holocaust, or, as many Jews know it as, the Shoah ("catastrophe") (Holocaust Museum).

End of War: After several key battles were lost, many nearby capitals were liberated, his closest allies were captured or defeated, and the first camp was liberated in 1944, Hitler began to lose control. In January 1945, Hitler retreated to his Chancellory in Berlin, hiding away in his bunker for 3 months. On April 30, he and his wife, whom he had married the night before, committed suicide in the bunker (Britannica).

-

Paul von Hindenburg:

Early Life: Hindenburg was born October 2, 1847 in Posen, Prussia (now located in Poland). At age 11, Hindenburg served as a cadet in the Austro-Prussian War and in the Franco-German War. Later in World War I, he served Germany as a superior to Erich Ludendorff, a strategist. When they successfully drove Russia out of East Prussia, he got the credit. And, when the US was drawn into the war after a failed submarine attack of their making, he convinced the country to blame his partner.

Rebuilding after World War I: Working with the new established republic, he focused on the safe withdrawal of German troops and the shutting down of "leftists". After gaining the country's love, he was elected as president. In his presidency, he authorized the country's parliament--the legislative body. He was reelected after running against Hitler in 1932 (Britannica).

Hitler's Chancellorship: Because the Nazi Party gained 37.4% of the vote in the Reichstag election, Hitler demanded that he become the Chancellor--Hindenburg refused but offered him Vice Chancellor, which Hitler angrily refused and withdrew Nazi support of the president. After the next Chancellor failed at uniting the country (37.4% had voted with the Nazis after all), Hindenburg was convinced to give Hitler the chancellorship and allotted him two Nazi seats in the cabinet, which were filled by Hermann Göring and Wilhelm Frick. Hindenburg's advisors assured him that Hitler would be easy to control.

Co-Workers: With Hitler as Chancellor, the "Enabling Bill" of 1933 was passed, making both men have dictorial power over Germany. Hindenburg, at 85, was idle. Hitler became a dictator (Holocaust Museum).

Death: Upon his death in 1934, Hindenburg was made out by Hitler's propaganda to be a huge Nazi supporter despite the evidence proving he was neutral at best.

-

Hermann Göring:

Early Life: Born January 12, 1893, Göring lived in a Bavarian (German state) castle with his family. He was trained from an early age to join the military and served in the air force during World War I. After Germany lost the war, Göring moved to Denmark, them Sweden, where he served as a commercial pilot.

Early Nazi Work: After meeting Hitler in 1921, Göring joined the Nazi Party in 1922 where he was given command of the Sturmabteilung, or the SA--an organization that provided physical protection for the Party.

Injury: After Hitler attempted to start a revolution at the Beer Hall Putsch in 1923. While Göring escaped his arrest by moving to Austria, he was wounded in the groin. Becoming dependent on morphine as a painkiller, Göring was admitted to a Swedish mental hospital twice for treatment.

Reichstag: Moving back to Germany in 1927, Göring occupied a Reichstag (parliament) seat for the Nazi Party a year later. When the Party was awarded more seats in following elections, Göring became the president of the Reichstag.

Hitler's Dictatorship: When Hitler became dictator following the Enabling Act, Göring was given new powers, which he used to create the Gestapo--the secret police--concentration camps for political opponents, and the Luftwaffe--Nazi air force focused on bombs rather than fighter planes.

Retirement: When his Luftwaffe failed to win key battles in the early 1940s--the bombs were meant for destruction, not protection--Göring retired to Carinhall, his estate that he shared with his second wife and only child. He lived a lavish lifestyle, collecting art (much of it stolen from Jews as they were ripped away from their possesion), and eating enough to gain a reputation for his size. His addiction to pain medication was still present. While the pills made him, along with his flamboyant eye for fashion, notoriously loud, excitable, and elated.

End of Power and Life: Believing Hitler to be swarmed and helpless in Berlin--he was, as it was days before his suicide--Göring sends a telegram to Hitler's bunker, asking him if he should take over power. Hitler called him a traitor, stripped him of offices, and called for his arrest (Holocaust Museum). When Germany surrendered, Göring was captured by US forces in Austria.

Trial: Put on trial for war crimes at the International Military Tribunal at Nürnberg, also known as the Nürnberg Trials, Göring defended himself, saying he had no knowledge of the "war crime" elements of his regime. He argued that Heinrich Himmler, who had taken over as operator of the secret police and concentration camps, had done all the work secretly. When found guilty, Göring was denied his request to be shot instead of hanged. The night before his execution, he took a cyanide pill that had been hidden in a jar of pomade. He died October 15, 1946 (Britannica).

-

Ernst Röhm:

Early Life: Born November 28, 1887 in Munich, Germany, Röhm served for years during World War I, getting injured 3 times--he acquired the rank of "captain".

Work with Hitler: Having been apart of the Nazi Party before Hitler joined, Röhm and Hitler became close comrades in 1919--even friends. Röhm supplied his troops of physical protection (which would later become the SA in 1921). His forces carried out the attempted revolution at Beer Hall Putsch, and Röhm was imprisoned briefly for his involvement.

The Night of the Long Knives: Röhm's plans for the SA (now totaling over four million men) was to join forces with the national army, something Hitler did not agree with, as he believed that the power that came with Röhm leading the national army would rival his own. Hitler much preferred the SS opposed to the SA, as he had more power over that group. Persuaded by his advisors as well as his own paranoia, Hitler shot and killed his friend in 1934 (Britannica). After killing Röhm, Hitler proceeded to kill 177 others--both fellow Nazis, political leaders, and citizens who he deemed as threats. This massacre became known as the Night of the Long Knives.

After Death: Röhm was deemed a traitor and an immoral person--his friends supposedly engaged in homosexual orgies and lavish lifestyles, making Röhm complicit in the taboo activities. Röhm and the SA were labelled as enemies, as Hitler stated they had been planning a revolution. By 1934, the SS, run now by Heinrich Himmler, fully replaced the SA in becoming Hitler's manpower (Holocaust Historcial Society).

-

Joseph Goebbels:

Early Life: Goebbels was born on October 29, 1897 in Germany to a Roman Catholic family. He did not serve in the military as he had a clubfoot, something that was a major insecurity. Not initially involved in politics, as he was focused on education and writing, Goebbels joined the Nazi Party and began writing a biweekly magazine.

Propaganda: Once Hitler rose to power, Goebbels was put in charge of propaganda. Through the magazine and speeches, Goebbels made Hitler out to be the best leader possible--through him, the "Führer" myth spread. Führer means "leader", and it was a title, much like "king" or "emperor". In the early 1930s, Goebbels was given control over all forms of media--books, radio, music, film, etc. It was him who corganized the infamous burning of "unGerman" books.

Anti-Semitism: Though he originally admired his Jewish teachers in university days, Goebbels hatred for Jews grew with his position in the Party. He organized films, such as the pseudo-documentary "The Eternal Jew", which depicted Jews as contagion carrying "rats", to convince citizens that Jews were. athreat to German prosperity. On November 9, 1938, Goebbels called for "spontaneous demonstrations" against Jewish citizens and businesses in response to the killing of a German diplomat by a Jewish student. People complied--on the day, known as Kristallnacht, or "Night of Broken Glass", mobs killed 91 Jews, burned 900 synagogues, destroyed 7,000 businesses, and forced 30,000 Jews into concentration camps (PBS).

Changing Tide: As Germany began to lose the war, Goebbels took an interesting route--instead of providing false hope or falsifying information, Goebbels told the truth while connecting events to past history, stating that there was still hope based on precedent of other wars.

Death: Following Hitler's suicide, Goebbels was named the next leader. However, on May 1, 1945, knowing the Nazis had lost, Goebbels tragically poisoned his six children with cyanide and committed suicide with his wife (Britannica).

-

Engelbert Dollfuss:

Early Life: Born October 4, 1892, Dollfuss studied law and economics before becoming involved in the Austrian Farmers’ Association, chamber of agriculture, and the Christian Social Party. In May 1932, he became chancellor of Austria.

Chancellorship: Dollfuss headed a near-authoritarian regime, as he compensated for not being well likes amongst Austrians. Citizens wanted to join withn Germany, something Dollfuss did not do--he angered Social Democrats, Pan-German nationalists, and Austrian Nazis. He allied with Italian dictator Mussolini, reenforcing a fascist government in Austria.

Death: Because he refused to listen to Hitler and the Nazis in their attempt to merge Germany and Austria, Dollfuss was assassinated in 1934 (Britannica).

-

Austrian People:

Either actively supporting or idle to Hitler's annexation of Austria, the Austrian people were conquests of Hitler.

-

Franz von Papen:

Early Life: Born October 29, 1879, grew up in a Catholic, landowning family. He served as a soldier in World War I before being caught by the US for espionage. He was released back to Germany, where he then served again as the chief of staff for the Fourth Turkish Army in Palestine.

Politics: Returning from war, von Paper joined politics. He was ultra-conservative and a monarchist. Due to help from President Hindenburg's advisors, he became the chancellor in 1932. He was an enemy of Hitler, as, though he did not have a large following himself, Hitler saw him as a threat.

Forced Out: After a string of his policies were denied by the Reichstag, von Papen was pressured to resign--he was replaced by Kurt von Schleicher. Angry at the situation, von Papen allied himself with Hitler, advocating successfully for his chancellorship in 1933--von Papen was made vice chancellor. He worked on Austria's annexation as an ambassador.

After the War: Von Papen was put on trial at Nürnberg with war criminal charges--while he was found not guilty, he was imprisoned for being an influential Nazi. He was sentenced to 8 years in prison, though he only served half of his sentence before he successfully appealed (Britannica).

-

Prussian Landowners:

Definition: "Junkers", or Prussian/East German landowners, were a political force during the time of Hitler.

Politics: Junkers were extremely conservative, monarchists, and agriculture focused individuals. Their opposition to the way that Germany was run pre-Hitler aided in his rise to power, as Hitler formed political connections with them (Britannica).

-

Middle Class Tradespeople:

Impact: The general public during Hitler's reign, their lack of opposition meant that Hitler easily took power.

Hitler

Göring

Goebbels

Hindenburg

Röhm

Dollfuss

Plot | Event

Cicero, 1920s

Plot Points

Reichstag Fire

-

Germany: Using Al Capone as the mobster inspiration for Ui, Capone's main territory was Chicago. Hitler already had power in Germany while he pursued power in other countries, just as Capone owned Chicago while he set sights on other areas.

-

Austria:

Using Al Capone's conquest of Cicero (near Chicago), Brecht parallels Hitler's conquest of Austria.

-

Hindenburg's Bribe:

The Junker's "gifted" president Hindenburg land. Hitler used this knowledge to blackmail the president.

-

In this monologue, Mark Antony is recounting the events of Caesar’s assassination to the citizens of Rome. Caesar was murdered by the senators, but the assassination was led by Brutus- Caesar’s close friend.

In the context of this show, Ui delivering this monologue foreshadows his eventual killing of Roma, where Ui acts as Brutus and Roma acts as Caesar. This creates an interesting dichotomy in which Roma, although acting as Caesar, leader of Rome, is not the one running the Chicago gangland.

Brecht further manipulates the roles within Julius Caesar by having Ui speak as Mark Antony about Brutus instead of having him read a Brutus monologue. Mark Antony was a friend of Caesar’s and was not directly involved in the assassination of Caesar; he was a witness, an observer. Audience to the killing of his friend.

Therefore, in this scene Brecht has put Ui in the position of both Mark Antony and Brutus. Perpetrator and bystander. He is a witness to his own crime. By adding this layer of abstraction, Brecht forces audience members not to be absorbed in the action of the scene but to think about their own complacency. It is commonly believed that those who do not fight oppressive systems are contributing. Plenty of people in Germany, Austria, and around the world stood by during Hitler’s rise to power and reign. This scene invites the audience to think about what injustices they are enabling passively.

-

Reichstag Fire:

On February 27, 1933, German's parliament building, the Reichstag, was destroyed due to arson. Hitler alleged that a communist man--Marinus van der Lubbe was a Dutch activist--stating that it was only the beginning of the destruction communists would bring to Germany. Van der Lubbe was found guilty, though some alleged he seemed drunk and/or drugged during his trial, and he was guillotined in February of 1934. Many now believe that the Nazis started the fire as a way for Hitler to gain influence, as the Reichstag Fire was the final act that pushed parliament into giving Hitler full authority (Britannica).

-

Night of the Long Knives:

After Hitler's trusted confidant and friend, Ernst Röhm, gained too much power with his SA troops, Hitler had him assassinated.

St. Valentine's Day Massacre:

Roma's killing in a garage resembles the infamous massacre, potentially led by Capone.

Vocabulary

Words and Terms

-

the world of organized crime

-

highest-ranking general (Italian)

-

describes someone excessively smooth-spoken

-

a morally repulsive or odious person

-

-

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer; a well-known Hollywood film company established in 1924. In its early days, it was especially famous for its musical films, made with great style.

-

very eager to spend money

-

wealthy to poor

-

Quickly

-

sold at an auction

-

The effects or consequence of an action or operation: product, result

-

converting (assets) into cash

-

Thompson submachine gun. A type of gun designed for trench combat in World War I, but it was not actually sold until 1921.

-

Nonsense

-

a situation in which people will do anything to be successful, even if what they do harms other people

-

Moving back and forth between two places, usually hurried and disorganized

-

Absent Without Leave

-

the unlawful taking of personal property with intent to deprive the rightful owner of it permanently

-

the act of taking something (especially money or property) from someone by force, intimidation, or undue or illegal power

-

treasury/funds OR a chest used for keeping money

-

Forget about it

-

used to refer to a situation in which someone can make a lot of money for very little effort

-

-

A common practice of exhibition shooters and pistoleros of the cowboy era, card shooting is an entertaining way to demonstrate your skills.

-

stomach

-

basic, fundamental, new, developing

-

carnations are a type of flower that symbolizes love. Giri showing up with carnations in his pinstripe suit is symbolic of him arriving with peaceful, good intentions

-

petty, small-time, trivial

-

(derogatory) disabled person

-

gangster’s girlfriend

-

money

-

a type of tree of the willow family

-

British spelling of check

-

shoot someone with a gun

-

prison

-

to appropriate (something, such as property entrusted to one's care) fraudulently to one's own use

-

in poor condition, shabby

-

handgun

-

outdated, behind the times

-

a person of high social position or outstanding competence

-

stop it (Italian and Spanish)

-

murdered

-

weakness, flaw

-

no chance, no way

-

honest and legal

-

information about someone or something that is not commonly or immediately known

-

excessively sentimental (mostly used to describe music or art)

-

a walk taken for one’s health

-

an area especially in a court of law where news reporters sit

-

any of numerous very small soft-bodied homopterous insects (superfamily Aphidoidea) that suck the juices of plants

-

of wholesome appearance

-

a group having a common nature or origin

-

bad handwriting

-

to associate familiarly

-

Someone important

-

an intentional, premeditated effort to undermine an individual's or group's reputation, credibility, and character

-

an expression indicating a lack of trust in somebody

-

to publicly express or show sorrow or regret for having done something wrong

the act of wearing a sackcloth and lying in ashes began as a Jewish repentance ritual

Read about sackcloth and ashes in the Hebrew Bible:

-

In the Hebrew Bible, a set of ten rules for all Jews (and later on, Christians) to adhere to. God gave them to Moses (Jewish prophet) on two stone tablets. Read the Ten Commandments (Exodus 20:1-17).

-

be fast in responding to a situation or understanding something.

-

to foretell especially from omens or to give the promise of

-

having the nap worn off so that the thread shows

-

Biblical figure from whom God took everything he had, but because of Job’s faith in Him, God restored it tenfold. Read the Book of Job.

Lobby Display Works Cited

“Al Capone.” FBI, FBI, 18 May 2016, www.fbi.gov/history/famous-cases/al-capone.

Apoyan, Jackie. “The Chicago Mob vs. Chicago Street Gangs.” The Mob Museum, The Mob Museum, 27 May 2016, themobmuseum.org/blog/the-chicago-mob-vs-chicago-street-gangs/.

“Bertolt Brecht: Poet and Communist.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 14 Dec. 2018, www.nytimes.com/2018/12/14/books/review/bertolt-brecht-collected-poems.html.

“Dr. Seuss Political Cartoons.” UC San Diego Library | Digital Collections, UC San Diego, library.ucsd.edu/dc/collection/bb65202085. Accessed 10 Oct. 2024.

“Gangland Map of Chicago.” The Vintage Map Shop, Bruce-Roberts Inc., 1931, thevintagemapshop.com/products/map-of-chicagos-gangland-1931.

“Golden Age of Radio.” WMKY, www.wmky.org/show/golden-age-of-radio. Accessed 10 Oct. 2024.

Historyradio. “The Golden Age of Radio Drama- It Never Ended.” Historyradio.Org |, 30 July 2023, historyradio.org/2017/12/04/remembering-the-golden-age-of-radio-drama/.

“January 6 U.S. Capitol Attack.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, inc., 3 Oct. 2024, www.britannica.com/event/January-6-U-S-Capitol-attack.

“Jennifer Wise.” UVic.Ca, University of Victoria, www.uvic.ca/finearts/theatre/people/profiles/emeriti/wise-jennifer.php. Accessed 10 Oct. 2024.

July 26, 2013. “Photo Gallery: A History of Cicero.” Photo Gallery: A History of Cicero -- Chicago Tribune, Chicago Tribune, galleries.apps.chicagotribune.com/chi-photo-gallery-a-history-of-cicero-20130725/. Accessed 10 Oct. 2024.

Macdonald, Fiona. “The Surprisingly Radical Politics of Dr Seuss.” BBC News, BBC, 2 Aug. 2022, www.bbc.com/culture/article/20190301-the-surprisingly-radical-politics-of-dr-seuss.

“Mercury Theatre On Air.” Orsonwelles.Indiana.Edu, orsonwelles.indiana.edu/items/show/1972. Accessed 10 Oct. 2024.

“Prohibition.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, inc., www.britannica.com/event/Prohibition-United-States-history-1920-1933. Accessed 10 Oct. 2024.

“Pro-Hitler Propaganda In Vienna.” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/photo/pro-hitler-propaganda-in-vienna. Accessed 10 Oct. 2024.

Rollin, Kirby. “This Will Help You Forget About The Peace Terms.” The New York World. March 18, 1919.

Punch Magazine. https://magazine.punch.co.uk/index/G0000c53YnqnGf60.

Stacker. “20 Photos of Chicago in the 1920s.” KESQ, 23 July 2022, kesq.com/stacker-lifestyle/2022/07/23/20-photos-of-chicago-in-the-1920s/.

“State of Deception: The Power of Nazi Propaganda.” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, exhibitions.ushmm.org/propaganda/home/state-of-deception-the-power-of-nazi-propaganda. Accessed 10 Oct. 2024.

Thale, Christopher. “Police: Policing in the 19th Century.” Encyclopedia Of Chicago, Encyclopedia Of Chicago, www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/983.html. Accessed 10 Oct. 2024.

“The Interwar Years.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, inc., 16 Sept. 2024, www.britannica.com/topic/history-of-Europe/The-interwar-years.

“The 2nd Article of the U.S. Constitution.” National Constitution Center, National Constitution Center, constitutioncenter.org/the-constitution/articles/article-ii. Accessed 10 Oct. 2024.

Wells, H.G. “The War of the Worlds.” The Project Gutenberg eBook of The War of the Worlds, by H. G. Wells, The Project Gutenberg, www.gutenberg.org/files/36/36-h/36-h.htm. Accessed 10 Oct. 2024.